One in Four

What my miscarriage taught me about loss, the body, and the myth of control

One in four pregnancies end in miscarriage, and so did mine.

At my nine-week scan, a heartbeat that had been there was no longer. I wasn’t shocked — that number, one in four, was something I’d been aware of from the beginning. But knowing the statistics didn’t soften the grief. Despite understanding the science behind why miscarriages happen, I still found my mind spiraling: maybe I had gone too heavy on squats at the gym, or maybe it was that one time I accidentally used a body wash with salicylic acid, or maybe it was all those days swimming in the Mediterranean.

My very kind OB-GYN reminded me that just because those thoughts appear doesn’t make them true. There was nothing I had done — or not done — that caused my miscarriage. Nearly all miscarriages that happen in the first trimester are caused by chromosomal abnormalities — errors in an embryo’s genetic material (too many, too few, or structurally altered chromosomes) that disrupt normal development.

For someone who has spent nearly a decade optimizing her health, accepting how little control I have over pregnancy outcomes has been humbling. By all measures, I’m exceptionally healthy: I eat well, I exercise daily, my sleep is dialed, my supplement stack is clinical, and I get more preventative scans than most people I know. But this is where the wellness industry, the whole optimization complex, paints a false picture. Constantly measuring, tracking, and optimizing your health doesn’t give you control — only the illusion of it. You can be the picture of health and still get cancer. Or a brain aneurysm. Or, if you’re a woman, a miscarriage.

More optimization isn’t always the answer, in the same way more data isn’t either. I love my data — I track everything — but trying to conceive and going through pregnancy loss showed me how flawed data can be. I used the Mira monitor to track my hormones and pinpoint ovulation with obsessive accuracy. It’s a fantastic tool for identifying fertile windows or spotting hormonal imbalances. But when I looked at my baseline hormone levels, the data suggested they were too low for me to conceive. Yet, I did — less than three months later.

It also didn’t matter that I was healthy and “optimized” when I faced unexpected complications from the D&C procedure after my miscarriage. When you miscarry, it can take weeks for your body to recognize that the embryo has stopped developing. There are usually no clear signs — no bleeding, no pain — and the diagnosis comes during a routine ultrasound, when no heartbeat is found or growth has stopped. It’s called a silent miscarriage.

You’re typically given three options: wait for the body to expel the pregnancy tissue naturally (which can take weeks), take medication to trigger the process, or undergo a surgical procedure (a D&C). I chose the procedure because I wanted a quicker recovery — physically and hormonally — so we could start trying again.

Yet again, my body didn’t cooperate. The physical recovery from a D&C is usually swift, but I experienced severe pain and bleeding that lasted nearly two weeks. This is rare and likely won’t happen to you, but it did to me. The complications didn’t end there: hCG, the pregnancy hormone, is supposed to gradually decline as the tissue clears, eventually returning to zero. Mine didn’t. For over a month, it stayed elevated, keeping my body in a kind of limbo — pregnant, but not.

Once the bleeding and pain subsided, I slowly regained my energy and resumed my normal routine. Recovery timelines vary — you might feel fine in a few days, or it might take weeks. Listen to your body.

The emotional recovery, on the other hand, is an entirely different beast.

Trying to become pregnant — becoming pregnant — is at once banal and miraculous. The moment you see those two lines on a pregnancy test, it becomes your center of gravity. You change what you eat, what you put on your skin, what you think about. And no matter how rational or data-driven you are, you start to imagine the future: a baby in your arms, a new life unfolding.

Pregnancy is perhaps the greatest test for anyone with anxiety or a need for control. Each morning you wake up wondering if you’re still pregnant. You live between fear and hope — praying nothing has gone wrong, while allowing yourself to dream. When the worst happens, what hurts most is the loss of the imagined future.

I felt it all: deep sadness, frustration that we were back to square one, fear of it happening again, guilt (even knowing I did nothing wrong), and that mean voice asking if something was wrong with me — too old, too broken.

There’s nothing I can say that will make emotional recovery easier, except this: you are not alone, allow yourself to feel everything, and avoid social media like the plague.

When I became pregnant, the algorithm turned into a pregnancy oracle I never asked for — endless videos of women detailing their morning routines, what they ate, what supplements they took, how they dressed, what they bought for their nurseries. Even when the content was benign, it was relentless. More problematic, however, were the horror stories — miscarriages, stillbirths, traumatic births. These stories matter. It’s important that women speak about what has for too long been silenced. But constant exposure to pain without context can be destabilizing. The algorithm doesn’t know what you need; it only knows how to keep you engaged. It connects you to experiences that have nothing to do with your own life, sometimes fostering empathy but more often amplifying fear.

The culture of sharing has blurred the line between expression and performance. I’ve seen women post videos the day their miscarriages happened — faces swollen from crying, voices trembling. I don’t judge them; I understand the impulse to make meaning out of something unbearable. But it also makes me wonder what happens to our grief when it’s lived out online, when every feeling becomes an offering to the algorithm.

Social media leaves no room for quiet — for sitting with what has happened and letting meaning form slowly. It rewards immediacy, not reflection. You’re expected to share before you’ve even processed, to narrate your grief before you’ve had time to feel it. Everything becomes content: even loss, even pain, even the most private moments of unraveling. There’s no space to hold something sacred or unfinished — to simply exist in silence without broadcasting it.

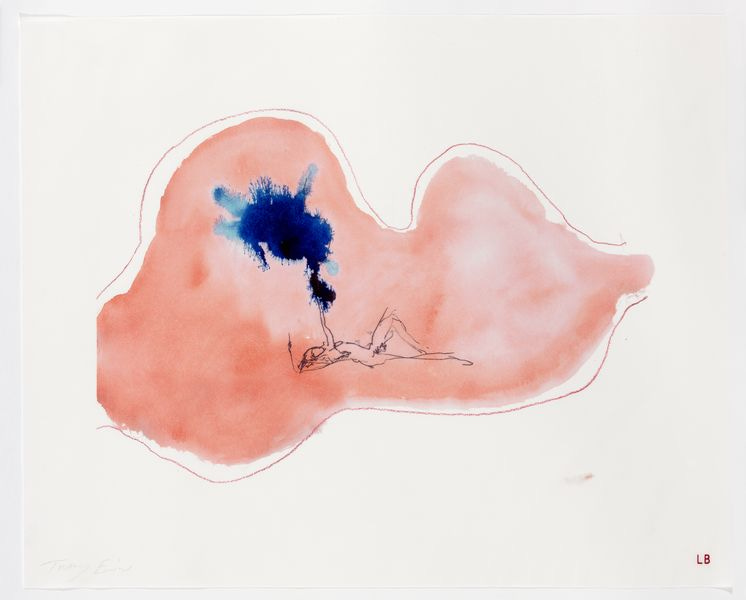

After all that noise, all that analysis, what remains is the body.

My body has slowly recalibrated. The bleeding stopped. My hormones almost leveled. I am still waiting for my period to return, to find that final piece of relief, the proof that my body is still functioning, even after what felt like betrayal. I will start tracking again, cautiously this time because I am no longer seeing data as truth, only as information. There’s a difference.

The hardest part isn’t the physical recovery; it’s learning to trust my body again. To believe that it hadn’t failed me, that it had done exactly what it was supposed to do: recognize that something wasn’t right and let it go.

Miscarriage doesn’t teach you a lesson; it just rearranges the way you understand control. You stop believing in guarantees. You learn that health isn’t immunity from loss. And yet, somehow, you keep going — walking every morning, eating well, sleeping, living. Healing isn’t dramatic; it’s just the quiet return to ordinary life.