Start up series part one: origin story

A five-part series on my experience building a consumer startup

After a couple of years of working on my startup, I decided it would be useful to synthesize some of my learnings from the process of building a consumer health business from scratch. To make this easy to follow, I’ll break it down into five parts:

Origin story and why finding PMF through the Y Combinator formula didn’t work for us

Why building a startup is much harder if you’re not technical

Fundraising lessons and crazy VC stories

Applying to and getting rejected by tech accelerators

Identity as a founder, pivoting, and whether it’s worth building a startup in 2024

Origin story and why finding PMF through the Y Combinator formula didn’t work for us

Around this time three years ago, my sister and I began spending many hours on zoom each day, brainstorming an idea. For months, we had both been struggling with unexplained health symptoms that ranged from minor inconveniences like headaches and fatigue to more painful ones like full body skin rashes, debilitating PMS, and depression. From extensive testing and hours spent talking to health experts, we understood this particular concoction of unpleasantness to be the result of underlying autoimmune and hormonal conditions.

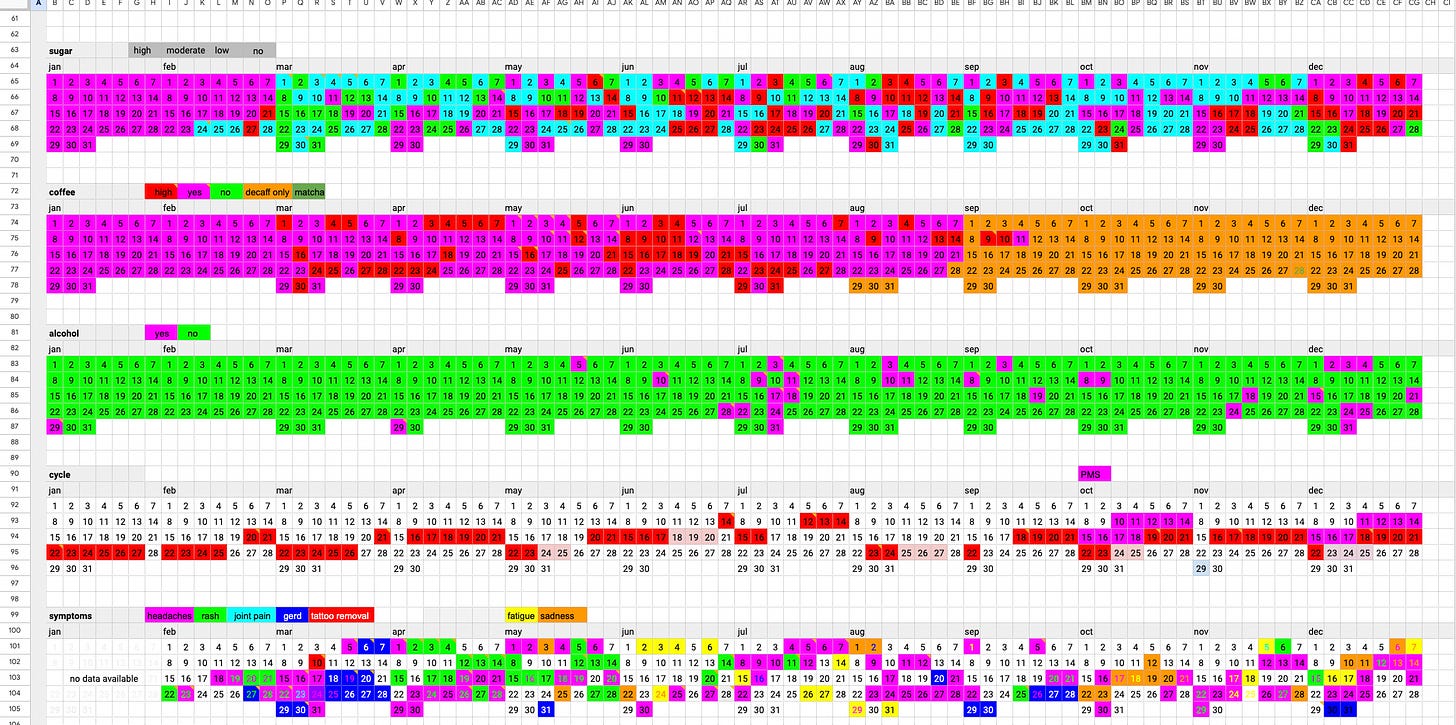

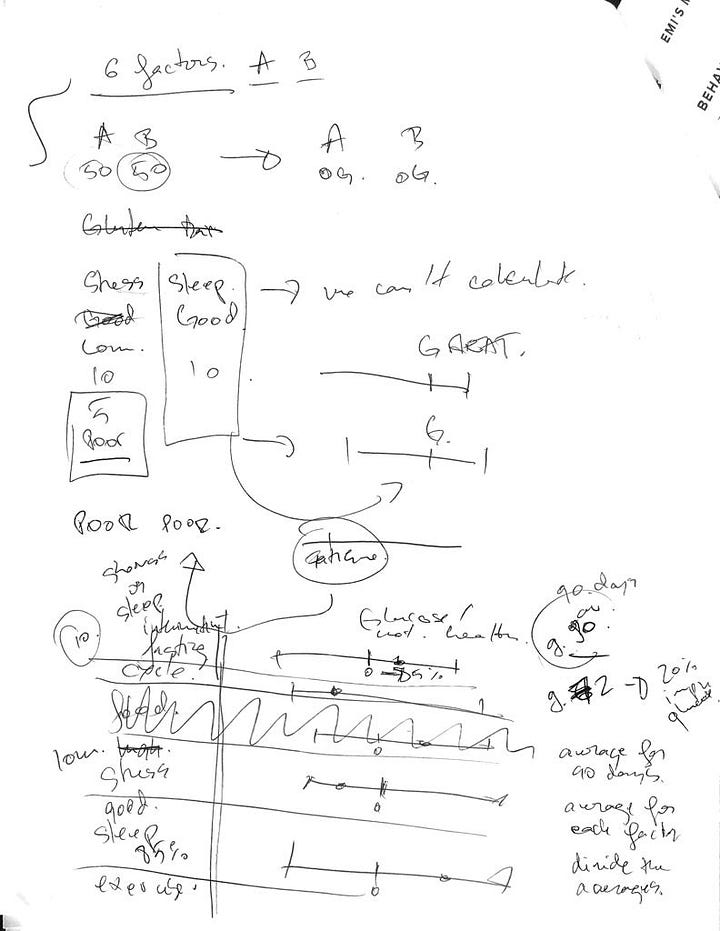

Various experiments ensued - from eliminating entire food groups to ingesting bagful of supplements, more testing, meditation and breath-work protocols, sauna and cold exposure, fasting and so on. And every single day, we minutely tracked each symptom, each lifestyle intervention and habit in a massive spreadsheet. But the more data we amassed, the more difficult it became to see patters and correlations. There had to be a better way to do this than spreadsheets, so we decided to build it.

It took us another nine months of research to formulate our vision for a product that would help women get to the root cause of their symptoms. Both Julia and I were already certified health coaches, but in the research process, we deepened our knowledge about the specifics of how autoimmune, hormonal and metabolic issues affect women disproportionately.

Aside from our personal stake in solving this, we also became deeply motivated by the lack of data in women’s health. In the US, until 1993, women were not legally required to be included in clinical trials which has created a huge gap and lack of parity on what drives many of the health issues women struggle with, as well as the potential solutions.

We put together a white paper documenting our findings and how we planned to address this problem. And we started wireframing a mobile app that would make health tracking super easy, and that would help women address symptoms caused by hormonal, autoimmune and metabolic problems. We decided to name it kahla, which means “well” in greek.

The story of how kahla was born is a common one: someone has a problem that is painful enough, that they can’t find a good solution to so they decide to come up with one, thinking that surely there must be others out there struggling with the same problem. When we described kahla to other women, the response was always along the lines of “I’ve been waiting for a product like this forever.” But we wanted to make sure we actually had a product, so we built an MVP and beta tested it in cohorts to get as much feedback as possible.

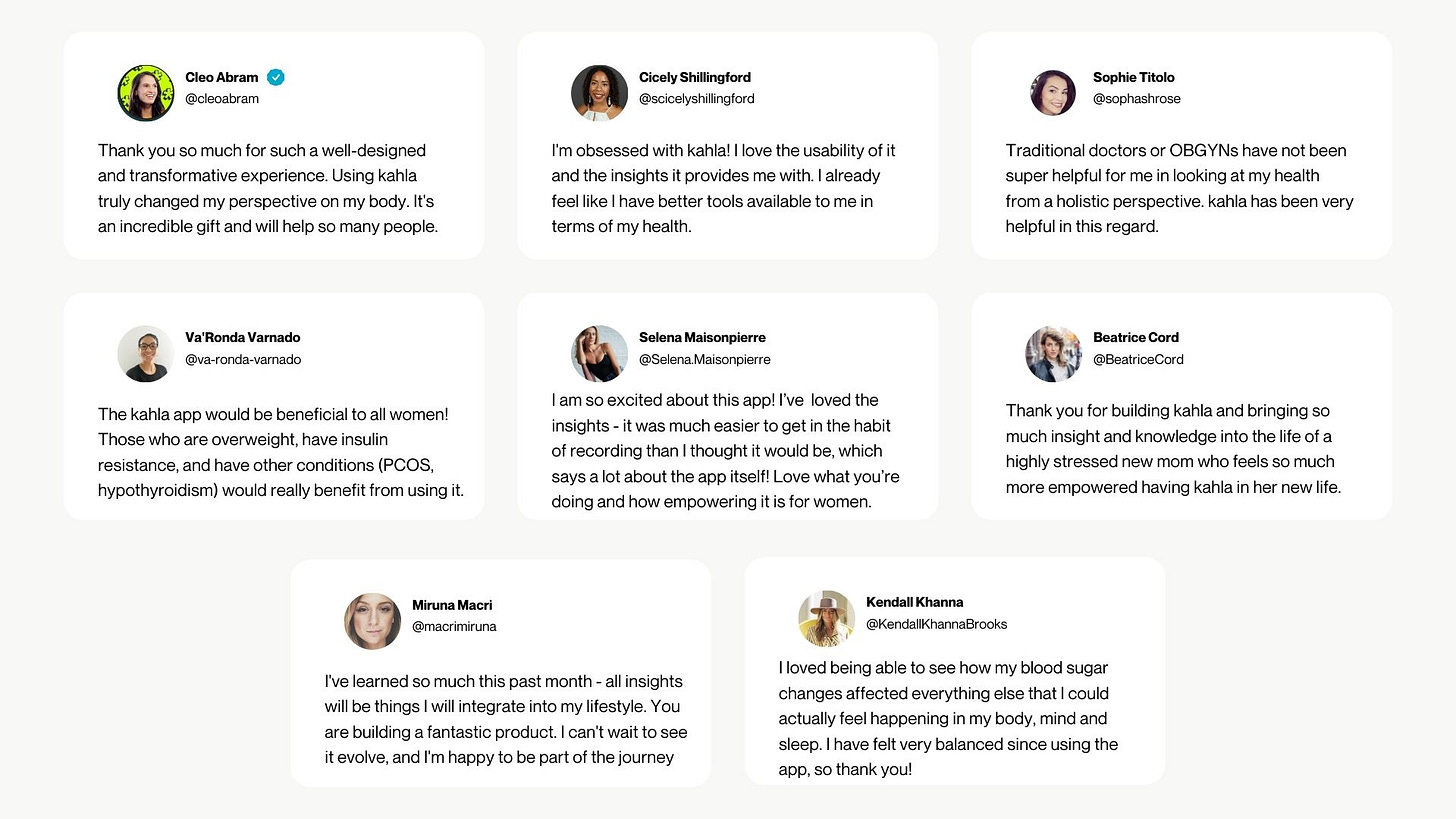

We started with ten friends, gave them the app paired with a CGM (continuous glucose monitor) to test for one month. We scheduled individual calls every week for the duration of that month to get feedback on the experience. We pressed on every single detail related to features, UI, UX, but also how women felt when they used the product - from their specific needs and questions to the more subtle emotions that came up. We knew women’s health could be tricky and complex.

The initial response was encouraging. Women loved how the app looked and felt - the most frequent comment we got was: “this really feels like an app made for women, unlike some of the other ones I’ve used that are designed for bros.” They also loved seeing data from their CGMs and how different foods, activities and lifestyle factors affected their blood sugar in real time. But mostly, it felt like they really enjoyed our 1:1 calls where after asking them for feedback, we would also provide health coaching based on the insights gathered in the app. Because we wanted to move really fast, the MVP didn’t yet have all the features we had dreamed up, so we were doing a lot of things manually - such as coaching.

Soon, the ten friends turned into hundreds of women, as we were getting referrals from nearly every user. That meant many weeks of back-to-back calls every single day, and collecting and analyzing tons of feedback. It was exhausting but more exhilarating than anything we’d ever done. We were also seeing promising engagement with 95% of our users spending on average 30 minutes per day in the app.

Up until that point we had followed lean startup advice and religiously played by the Y Combinator rulebook: solve a problem you understand, build for yourself, find more people that have that same problem, talk to your users, move super fast, iterate, iterate, iterate. Every time our users reported a bug or told us about a feature that could be simplified, we immediately prioritized for improving the user experience. We were also obsessed with growing organically and focused on word of mouth and referrals. We knew that we should not spend a single $ on acquiring customers before we had at least 100 users who were in love with our product.

We also made some big mistakes:

We gave out beta testers CGMs for free. Yes, consumers are overwhelmed by demands for their attention and money and it’s hard to get people to give you either. But sometimes, offering a free product - be it just for testing purposes - creates a false incentive and a sense of excitement that can be over-inflated.

The coaching portion of our feedback calls was also a mistake because we failed to measure how much value our beta testers were getting from - essentially - another free perk. Getting those insights directly from us minimized the effort they had to make in order to receive the same insights from the app itself.

When we saw engagement drop after a few weeks of using the CGM (as expected), we asked users what other features would make them use the app every day. When the majority said a menstrual tracking feature, we believed it.

The CGM part was very useful in confirming a hypothesis we had from the get-go: when we started charging for it, users were willing to, and excited to buy one for the first month, but not necessarily repeat the purchase. For this reason, we had made the CGM an optional rather than central feature. Integrating multiple external metrics provided users more datapoints, but the app was designed to give you enough without the CGM. What it did bring, however, was the magic of getting data without having to do anything. In the same way that slipping on an Oura ring or Whoop band can provide insights with zero effort, the CGM was providing a thrilling, gamified experience to seeing one’s blood sugar data in real time. As with everything shiny and new in life, the thrill died after a few weeks and most users felt there was no value in continuing to use a CGM once they understood what impact certain foods or activities had on their blood sugar. Some kept buying CGMs because they enjoyed the Hawthorne effect of wearing one and felt that it provided a system for accountability. Those were less than 5% of users.

Over the next couple of months, we built all the features that our users requested - menstrual tracking, easier meal logging, ad-hoc symptom journaling and more. With every new feature, we were measuring cohort engagement and hoping that we would see it, if not skyrocket, at least stick. We were confident about the menstrual tracking feature - not only it had been the most requested one, but we believed that by giving women, daily, personalized recommendations based on their unique cycle data, we could replicate the magic of getting value with very little effort in return.

What we learned, to our unpleasant surprise, was that even though women had requested a menstrual tracking feature, when it came to actually using it, the response was often “I can’t be bothered to track it every month”. The thing is, in order to receive the recommendations, you still had to make a bit of effort in logging your cycle data. Perhaps the most valuable lesson from the process of building a consumer product is that what people tell you they want rarely matches what they’re willing to do in order to obtain it. Even as we made the tracking as automated as possible (pulling data from Apple health and other devices), the kahla app was still not as simple as wearing an Oura ring, taking a supplement, or having an expert give you a plan that all you had to do was follow.

Here’s something that no Paul Graham essay prepares you for: you can find people who have the same problem as you, but that doesn’t mean the same solution that worked for you will also work for them. Sure, women had painful, unexplained symptoms, but they also did not have time or energy to track, log and measure a bunch of health metrics. Julia and I thought about ourselves as proactive and interested in health. What we failed to realize was that we had more in common with male biohakers than with most other women.

In theory, in 2024, society has embraced a proactive mindset vis-a-vis health. But in practice, our lifestyle choices are still very much driven by either vanity (working out, weight loss), or solving an acute problem (pain), fast. The promise of a miraculous drug or supplement, or diet, especially when promoted by an expert - or more dangerously - by an influencer with a large audience, is often far more successful at extracting money from consumers than a product that involves effort from users over a sustained period of time.

Another harsh lesson we learned was that in 2024, even having a well designed product priced very low (less than $10/ month) does not beat having distribution (aka an audience). Fellow founders in the consumer space that we spoke with shared our frustration with mediocre products that had more reach because they were started or promoted by people with large audiences. Some were able to hack growth, but only to a certain point and with very low repeatability across other products. If, for example, community building worked like magic for one type of consumer product, it seemed to have absolutely no impact for others. The lucky ones who were able to raise VC money before 2022 were acquiring customers at huge costs, with CACs often four times higher than LTV.

So if building for yourself doesn't always work, if solving a problem also doesn't always work, and if extracting money from consumers is harder than you think, how can you expedite the learning curve? It took Julia and I over a year to build our MVP, talk to users and iterate on a multiple versions of the kahla app. We could have accomplished all of this faster if we were engineers. More about why being a technical founder can save you a ton of money and time in part two of this series.