Why you should care more about your 50 year-old body than your beach body

Body composition vs. weight and how to maintain your long-term health

You know those people who will proudly tell you that at 50 they weigh the same they did at 20? I usually say “congratulations” and refrain from breaking it to them that they’re probably fatter than they were at 20. In today’s culture, the word “fat” has become extremely contentious and the more anodyne “weight” is used liberally when in fact, fat and fat distribution are far more consequential for metabolic health than weight.

The reason why you may be fatter at 50 than you were at 20 despite weighing the same is because muscle mass and strength decline with age, a process known as sarcopenia. The rate and onset of this decline can vary, but here are some general points:

Starting Age: Muscle decline typically starts around the age of 30 and we can lose approximately 3-5% of our muscle mass per decade if we do not engage in strength training or other muscle-preserving activities.

Acceleration: The rate of muscle loss often accelerates after the age of 50, increasing to about 1-2% per year.

Hormones: Changes in hormone levels - for both women and men - such as decreased testosterone, estrogen and growth hormone, contribute to muscle loss.

Body Composition: Muscle tissue is denser than fat tissue. Muscle has a density of approximately 1.06 grams per cubic centimeter while fat tissue has a density of about 0.9 grams per cubic centimeter. So a person with higher fat content and less muscle may weigh less than a person with more muscle mass and less fat.

The problem with BMI

General health guidelines have done us no service by placing so much emphasis on BMI vs. body composition. Body Mass Index (BMI) is the numerical value derived from an individual's weight and height. It has been widely used as a simple and quick screening tool to categorize individuals based on their body weight relative to their height. But BMI is an incomplete or imprecise measure of metabolic health for several reasons:

BMI Formula: BMI is calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. It does not distinguish between weight from muscle and weight from fat.

High muscle mass: Athletes or individuals with high muscle mass may have a high BMI but low body fat, leading to an overestimation of their health risk.

Low Muscle Mass: Conversely, individuals with low muscle mass but high body fat may have a "normal" BMI but still be at increased risk for metabolic diseases.

Visceral Fat vs. Subcutaneous Fat: BMI does not account for where fat is distributed in the body. Visceral fat (around the organs) is more closely associated with metabolic diseases than subcutaneous fat (under the skin).

Blood Pressure, Cholesterol, and Glucose: These markers provide direct information about metabolic health. Individuals with a "normal" BMI might still have high blood pressure, cholesterol, or glucose levels.

Inflammation and Insulin Resistance: Conditions like chronic inflammation and insulin resistance, which are critical indicators of metabolic health, are not captured by BMI.

BMI can provide a general indication of metabolic health risk across a given population, but at an individual level, you need a more comprehensive set of measurements to assess your metabolic health. The metrics you should pay attention to include:

Body Fat Percentage: To distinguish between fat and lean mass.

Fat Distribution: Abdominal or visceral fat (fat around the organs) vs. subcutaneous fat (fat under the skin).

Blood Tests: To check glucose and insulin levels, lipids, and markers of inflammation.

Blood Pressure: To evaluate cardiovascular risk.

Subcutaneous Fat vs. Visceral Fat

Subcutaneous fat is located just beneath the skin, distributed throughout the body but commonly found in the hips, thighs, butt, and abdomen. This is the type of fat we tend to get fixated on because it’s more noticeable and often the focus of our vanity concerns. But despite our cultural and societal aversion to body fat, this type of fat is generally associated with a lower risk of metabolic diseases compared to visceral fat and can serve a protective role by acting as a cushion for the body and as an energy reserve.

Visceral fat, on the other hand, is located deep within the abdominal cavity, surrounding internal organs such as the liver, pancreas, and intestines. This is the type of fat you cannot see as it is stored around organs, not under the skin, but it’s the most dangerous as it’s more metabolically active than subcutaneous fat. It releases fatty acids, inflammatory markers, and hormones directly into the portal circulation, which leads to the liver. Visceral fat is associated with a higher risk of metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and certain cancers.

Even lean people with a low total body fat percentage can have a significant amount of visceral fat that they wouldn’t know about unless they took a body composition measurement.

How to determine body composition

Determining body composition accurately involves measuring the proportion of fat, muscle, bone, and other tissues in the body. The gold standard for assessing body composition are MRI or CT scans, but these tools are impractical because they’re not typically used solely for body composition analysis and the cost is prohibitively high. Other effective methods include DEXA scans, Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA), skinfold calipers, and waist circumference measurements.

DEXA scan

A DEXA scan is the next best thing if an MRI or CT are not viable options as it’s considered one of the most accurate methods for measuring body composition. It provides detailed information about bone density, lean muscle mass and regional body fat distribution, including visceral fat.

Despite involving X-rays, the radiation doses associated with DEXA scans are significantly lower than those from CT scans, amounting to only about 0.003 mSv for a whole-body scan. For comparison, a flight from Los Angeles to New York exposes you to approximately 0.035 mSv, while a flight from Los Angeles to Tokyo exposes you to around 0.054 mSv. The cost of a DEXA scan typically ranges from $100 to $300, depending on the location.

BIA

Commonly used by smart scales for the home, Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis measures the resistance of body tissues to electrical currents, which can be used to estimate body composition. This measurement is less accurate than DEXA, but it’s widely available and relatively inexpensive.

Skinfold Calipers

This is a small device that measures the thickness of skinfolds at various body sites to estimate body fat percentage. It’s inexpensive and portable, but requires a skilled technique, and can be less accurate for very lean or very obese individuals.

Waist circumference

This is a quick, inexpensive measurement that can be done at home using tape to measures the circumference of the waist, typically at the level of the navel. Waist circumference has been found to correlate reasonably well with visceral fat deposition. However, since waist circumference measures both subcutaneous and visceral fat, it does not specifically quantify the amount of visceral fat, which is the most critical for assessing health risks.

How to improve body composition

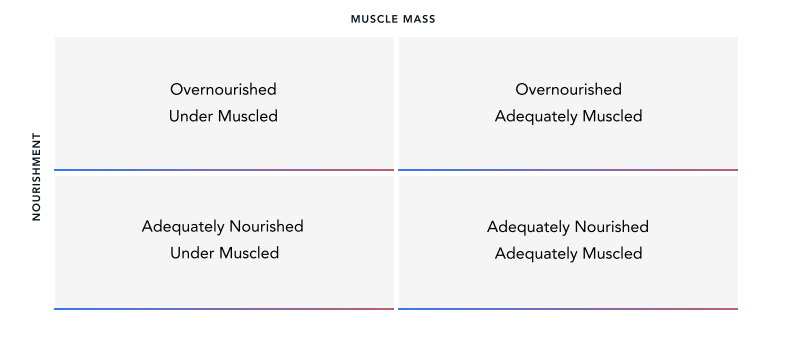

To decide how to improve your body composition, I like the framework proposed by Peter Attia:

Under Muscled and Overnourished - aka overweight or excess fat

Control energy intake (calories) and eat enough protein to promote muscle growth.

Liftweights/resistance train to build muscle, but increase cardiovascular exercise, as well.

Adequately Muscled and Overnourished - aka overweight or excess fat

Control energy intake (calories) particularly if high visceral fat is a concern. If visceral fat is not high, choosing to restrict calories is primarily for aesthetic and/or orthopedic injury purposes. If you choose to restrict calories for weight loss, it is okay to be at the lower end of protein intake, but don’t compromise protein so much that it becomes difficult to build or maintain lean mass.

Continue with weight lifting/resistance training but increase cardiovascular exercise.

Under Muscled and Adequately Nourished - aka “skinny fat”

Focus primarily on increasing protein intake. If you happen to be undernourished, increase overall calorie intake in addition to protein intake. If you’re adequately nourished, increase protein while keeping total calorie intake roughly constant.

Increase the amount of weight lifting/resistance training you’re doing, and if you’re doing a lot of cardiovascular exercise, consider reducing it.

Adequately Muscled and Adequately Nourished - aka strong

Keep at it. Focus on going deeper into your exercise and nutrition goals and fine tuning training and nutrition.

Strong rather than “skinny fat”

Vanity is often a stronger fuel for motivation than long-term health. And I get it. We all want to look good - even when “good” is informed by society’s unrealistic standards. For most of my teenage years and 20s I, too, was fixated on my weight and my happiness seemed to fluctuate with the couple of pounds I gained or lost. But when I turned 30, I became more invested in my health and started working on improving my body composition which led to some unexpected results: I now weigh more than I did in my 20s, but I look better because I have more lean muscle mass and less fat which means I am more toned, my posture is better and I appear leaner.

I will never be super lean because that’s just not my body type and as much as we love to praise discipline and willpower, if you’re 5’4” and naturally have a bigger but and hips, well, you’re not going to look like Kendall Jenner no matter how little you eat or how many hours you spend in the gym. But you can maintain a healthy weight and a strong-looking body by paying attention to body composition which will really make a difference as you age.

For women, in particular, the hormonal changes triggered by menopause can further accelerate muscle loss and slow down metabolism. If right now you’re surviving on 1200 calories a day and not working out, or doing cardio exclusively to keep your slim figure, that might backfire when you’re 40 and the pounds start piling on while you eat less and less. Not only does muscle protect our bones, but it also improves metabolic rate and increases energy expenditure.

It’s hard to not be attached to the number we see on the scale, but deep down, it’s not about numbers. It’s about feeling good and confident. Great posture, firm skin, toned arms and legs, stamina, energy and vitality will actually make you feel more beach-ready - or more importantly - life-ready than a lower number on the scale.

An important final note:

If you are overweight as determined by a comprehensive body composition assessment, decreasing total fat is crucial not just in order to reduce visceral fat, but to reduce all health risks associated with being overweight including: heart disease, hypertension, stroke, type 2 Diabetes, osteoarthritis, certain cancers, infertility, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), chronic inflammation, and decreased life expectancy.