Obesity epidemic part two: preventing child obesity as a long-term strategy

How we are approaching prevention today and what we can improve.

Intro

If you want to learn more about the the unprecedented rise in obesity and the current gold-standard treatments, read part one of this series here. In part two, I will share data on how we approach prevention today and why I believe focusing on child obesity could be one of the most powerful interventions to date.

Obesity prevention today

The WHO Acceleration Plan to Stop Obesity states that:

Overweight and obesity are largely preventable, but tackling obesity must be recognized first as a societal rather than an individual responsibility with the solutions to be found through the creation of supportive environments and communities that embed healthy diets and regular physical activity as the most accessible, available and affordable behaviors of daily life.

So far, unfortunately, prevention efforts have struggled to keep pace with rising obesity rates. As of today, no country is on track to achieve the global nutrition target to stop the rise in overweight and obesity among children under 5, nor to achieve the global non-communicable disease target to stop obesity among adolescents and adults. This failure can largely be attributed to government policy, public health, and the medical system, but not only to these domains.

Shifting the responsibility and blame from individuals to society has positive implications, such as recognizing obesity as a disease, which can lead to appropriate treatment and reduced stigma. However, implementing effective, large-scale policies is a long and complex process. Without individual accountability, overcoming the obesity crisis may never be possible.

There are two primary reasons to focus on addressing childhood obesity. First, children and teenagers who are overweight or obese are significantly more likely to remain obese into adulthood compared to their peers with a normal BMI. Second, as explained in part one of this series, it becomes more challenging for these individuals to lose weight once they reach adulthood. While new medications, such as GLP-1 receptor agonists, and bariatric surgeries can successfully treat obesity and related health issues, these treatments come with both financial and health-related costs.

What contributes to child obesity

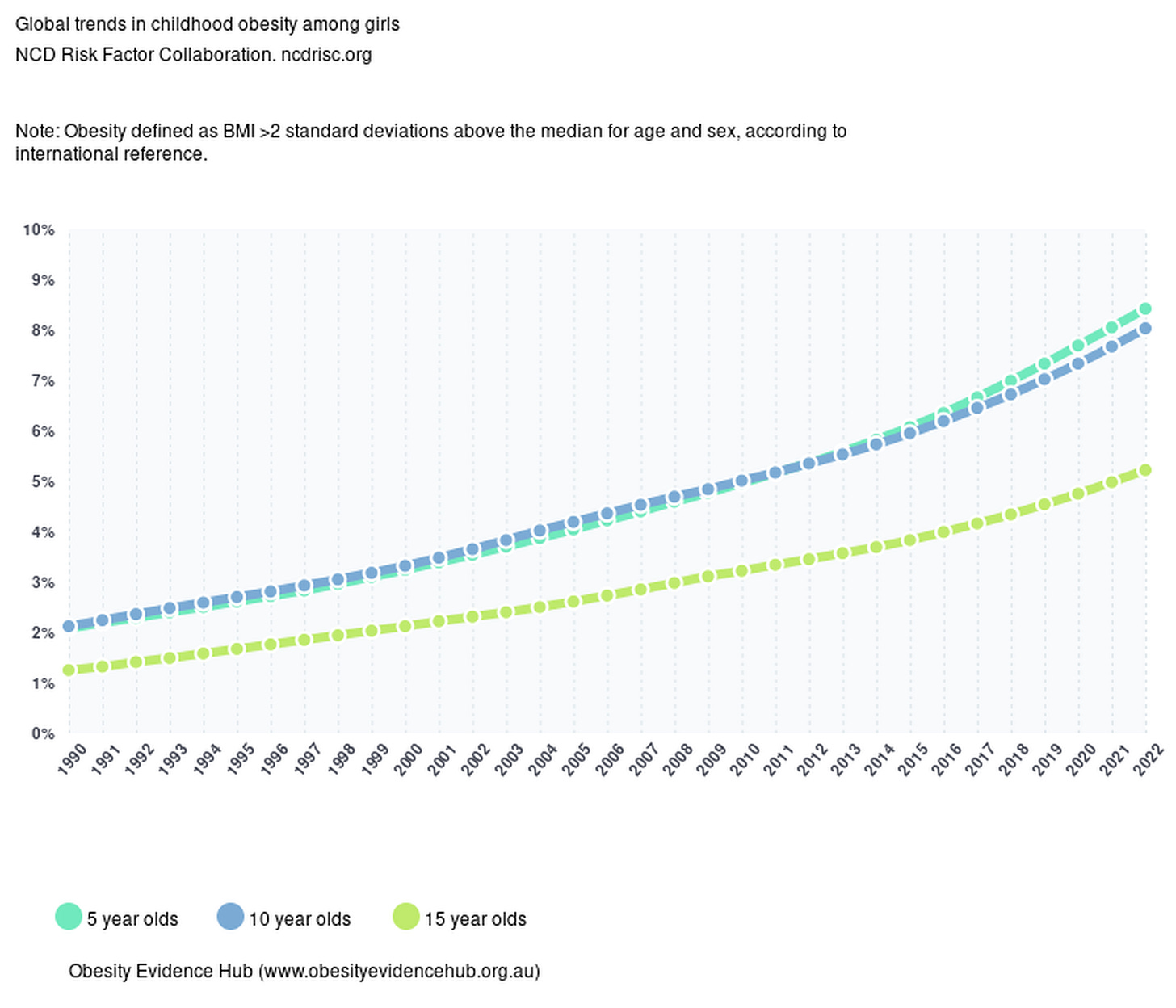

The rise in childhood obesity has seen a dramatic increase over the past few decades. According to the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration, in 2022, 65.1 million girls and 94.2 million boys aged 5-19 were living with obesity worldwide. The global prevalence of obesity in girls increased from 1.7% in 1990 to 6.9% in 2022, and from 2.1% to 9.3% in boys during the same period.

The main risk factor associated with being overweight as a child is the increased likelihood of developing obesity as an adult. Childhood obesity also leads to higher chances of developing type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and psychological issues, which can persist into adulthood.

The rise in childhood obesity rates is attributed to a number of interconnected factors. Sedentary lifestyles, unhealthy eating patterns, increased screen time, as well as socioeconomic and psychological factors are the main contributors.

Lack of physical activity

It is recommended that children and adolescents aged 6–17 years should achieve ≥ 60 minutes of physical activity each day. Unfortunately, only 21.6% of children 6–19 years reach the recommended 60 minutes of physical activity at least five days per week.

The link between reduced physical activity and weight gain was most evident during the COVID-19 pandemic when obesity rates among children aged 7 to 9 increased. A 2024 WHO/Europe report, conducted across 17 European countries with over 50,000 children participating, revealed that the pandemic led to more screen time and 30% less physical activity compared to the pre-pandemic period. This reduction in activity was accompanied by an increase in the number of overweight children in the same age group.

Poor nutrition

Children's diets have shifted towards higher consumption of calorie-dense, nutrient-poor foods. The availability and marketing of fast food, sugary snacks, and beverages have increased, leading to higher calorie intake without corresponding nutritional benefits. The WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative analyzed over 132,489 diets of children across 23 European countries and reported that fewer than half (42.5 %) consumed fruit and less than a quarter (22.6 %) consumed fresh vegetables daily.

Increased screen time

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), children in the United States spend an average of the following (shocking) hours per day in front of screens, depending on their age:

8–10 years old: 6 hours

11–14 years old: 9 hours

15–18 years old: 7.5 hours

Aside from its impact on obesity and cardiometabolic issues, average daily screen time is now considered an independent risk factor for disease and it has been linked to delayed cognitive development and increased depression among adolescents.

Socioeconomic factors

Children from lower-income households are more likely to be obese. Economic constraints can limit access to healthy foods and safe environments for physical activity. In the US, there are disparities in obesity rates among different racial and ethnic groups, with higher prevalence observed in Hispanic and Black children compared to their White and Asian peers.

The environment in which children live, including their home, school, and community, influences their eating and activity behaviors. Factors such as the availability of recreational spaces, community safety, and school policies on nutrition and physical activity also impact a child's risk of becoming obese.

Psychological factors

In a study exploring the connection between stress and childhood obesity, stress is identified as a key factor in both contributing to and perpetuating obesity in children. Children who are obese are more likely to encounter stress at home, and this daily stress can significantly influence their eating habits. Often, food becomes a coping mechanism for managing stress, anxiety, or other negative emotions, which can create a cycle where eating is linked to emotional relief.

A potential connection to the stress response is poor emotional regulation. In this context, a child's actions and behaviors are influenced by their emotions, how they experience them, and how they express them to others. Ineffective emotional regulation has been linked to stress and obesity, indicating that stress combined with poor emotional regulation can lead to unhealthy eating behaviors like emotional eating and other maladaptive behaviors such as sleep difficulties or decreased physical activity.

How to prevent child obesity

Evidence supports a multi-component, collaborative approach as the most effective prevention strategy. This approach involves societal measures, community and school programs, primary healthcare, and home/family-based interventions that integrate both physical activity and diet. Some interventions, such as preventative screenings, regular BMI assessments, and counseling sessions to educate families on healthy lifestyle choices, are easier to implement. In contrast, at-scale policy changes are more complex, expensive, and take longer to set in motion. Regardless of the type of intervention, the data clearly indicates one influential factor: parents have the power to adopt daily, evidence-backed practices that can significantly impact their children’s health.

Societal measures

The WHO Acceleration Plan to Stop Obesity proposes the following at-scale solutions:

Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels: implementing clear and effective labeling to help consumers make healthier food choices.

Restrictions on Marketing: limiting the marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages, particularly to children.

Fiscal Measures: utilizing taxes and subsidies to reduce the consumption of ultra-processed foods and beverages.

Healthcare Services: providing comprehensive services for the prevention and management of obesity within healthcare systems

Studies indicate that Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels (FOPNLs) such as the Guideline Daily Amounts (GDA), Traffic Light System (TLS), and specially designed labels can help children identify healthier snack options. The magnitude of improvements, however, is often small and context-dependent. For example, in France, the Nutri-Score label has shown positive effects on consumer purchasing behaviors, but these effects are modest.

Marketing restrictions have been shown to decrease the appeal of unhealthy foods to children, potentially reducing their consumption. Countries like Chile have implemented strict regulations on marketing unhealthy foods to children, including bans on advertising during children's programming and restrictions on using cartoon characters on packaging. However, comprehensive data on the direct impact on obesity rates in children is still emerging.

As of 2024, around 50 countries or jurisdictions have implemented taxes on sugary drinks. In the UK, for example, the sugar taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) led to a 28.8% reduction in sugar content of taxed beverages between 2015 and 2018. While reductions in SSB consumption are a positive step towards addressing obesity, the direct impact on childhood obesity rates is more challenging to measure in the short term. Long-term studies are needed to assess the full impact of these fiscal measures on obesity trends.

The implementation of such measures is even more critical in low economic status countries experiencing the fastest rise in obesity levels. The WHO timeline for achieving significant impact is set for 2030, with mid-term targets in 2025. However, no member state in the European Region is on track to reach the target of halting the rise in obesity by 2025. Societal measures alone cannot be the sole solution.

School and community measures

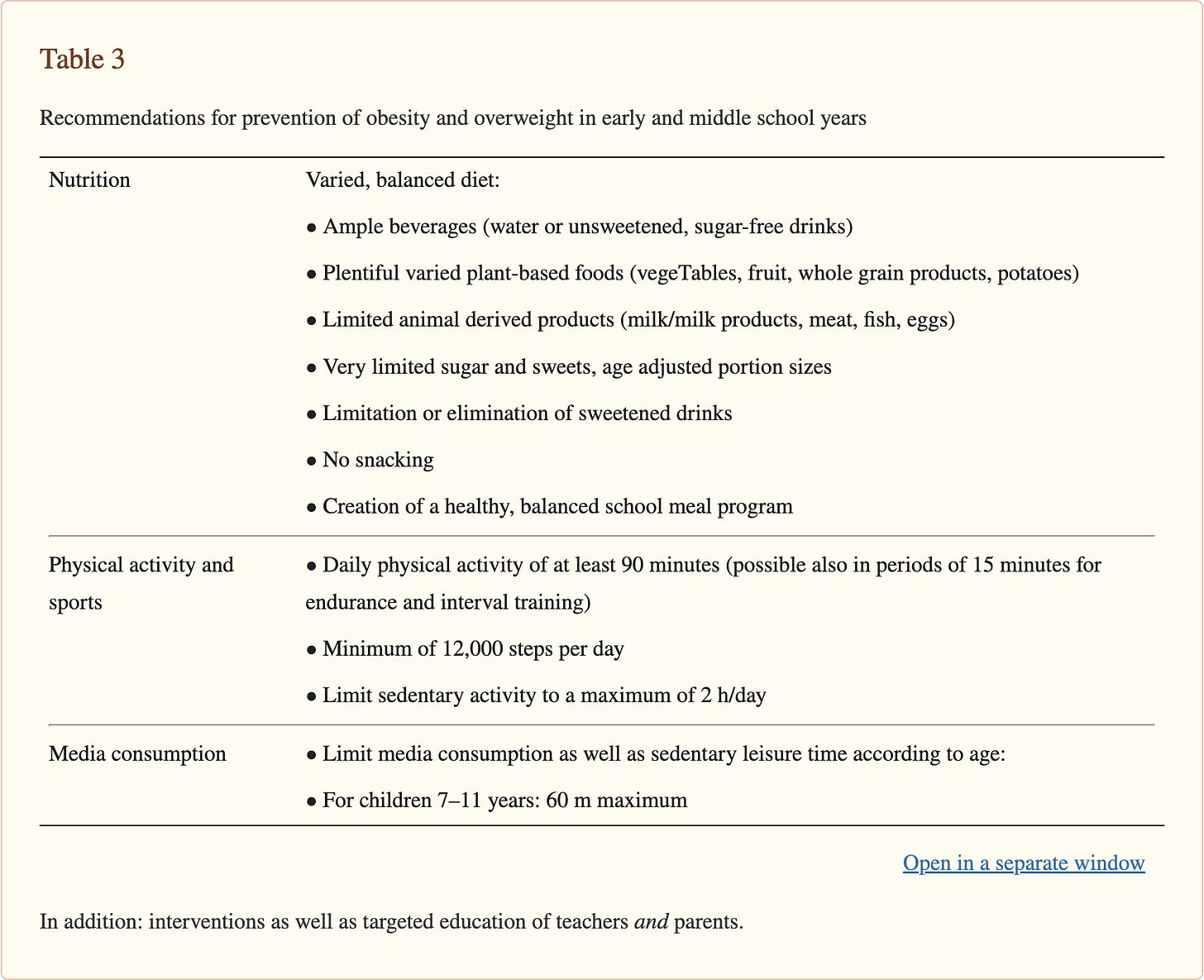

Some of the most effective school-based interventions include:

healthy nutritional behavior education, physical activity, and involvement of the parents

increasing the number of hours for physical education in schools and the development of extensive motor skills starting at a pre-school age

improvement of the quality of the catering offerings and removing vending machines

reducing the consumption of sugared beverages by offering drinking fountains

School-based prevention programs are effective in combating obesity due to the consistent interaction between children and teachers, especially when teachers act as role-models and get actively involved in health-promoting activities. These programs can blend behavior-focused strategies, such as nutritional education and promoting physical activity during regular classes, with environment-focused measures. This combination includes providing supportive facilities within the school setting, such as playgrounds, drinking fountains, healthy school meals, and nutritious snacks.

It has been shown that school-based programs offered for more than 1 year have the most beneficial effect on weight status and that combining nutritional education with an increase of physical activity leads to better outcomes. Focusing solely on nutrition or physical activity diminishes the effects.

Among the most relevant predictors for positive outcomes are the strong involvement of the parents. In Denmark, for example, which has one of the lowest rates of child obesity in Europe, there is no national school meal program, and most primary school children bring packed lunches from home. Some municipalities, like Copenhagen, have invested in school meals, which are paid for or partially paid for by parents. These meals are mostly organic and include dishes like salmon, pasta, porridge, and curry, with a focus on vegetarian options and minimal red meat. Snacks often consist of healthy grains and greens, such as dark rye bread, homemade rolls, fruits, or vegetables.

Home interventions

Research shows that the home environment is one of the most powerful influences on children’s healthy behaviors and overweight/obesity outcomes. Early childhood presents a unique opportunity to establish healthy lifestyle behaviors, such as good eating habits, regular physical activity, and limited sedentary time. This is particularly important because childhood obesity often continues into adulthood, with overweight preschool children being more likely to become overweight adults compared to their peers who maintain a normal weight.

At an individual level, parents can adopt preventive interventions at each step of the life cycle, starting from pre-conception and continuing during the early years. These include:

Perinatal: mother’s weight, adequate prenatal nutrition, healthy blood sugar levels during pregnancy, adequate postpartum weight loss

Infancy: exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months followed by inclusion of solid foods, providing a balanced diet with avoidance of calorie-rich, processed snacks

Preschool: model healthy food preferences by giving early experience of different foods and flavors, encourage behaviors around healthy eating, physical activity and sleep hygiene regardless of current weight status, monitor the rate of weight gain

Childhood: monitor weight and height, continue encouraging the healthy behaviors from above with an emphasis on physical activity, limit consumption of sugar sweetened beverages and energy-dense foods, limit screen time, support emotional self-regulation

Adolescence: as above, with an emphasis on preventing the increase in weight after growth spurts

Takeaway

The data clearly shows that fostering healthy lifestyle habits during early childhood is crucial for preventing overweight and obesity. The habits with the biggest impact are daily physical activity, a diet with very limited processed foods, snacks and sweetened beverages, minimal screen time, and emotional self-regulation.

However, these home-based interventions are easier to implement for parents with higher education levels, as research consistently shows a significant relationship between parental education and childhood obesity. Higher parental education levels are generally associated with lower rates of child overweight and obesity. This association follows an inverted U-shape across childhood, peaking around age 8 and narrowing in adolescence.

Given the critical importance of establishing a healthy foundation in that narrow timeframe, it is essential to implement measures that support and empower parents from lower socioeconomic or educational backgrounds. These efforts will be vital for addressing obesity prevention on a larger scale.